Walking on Quicksand

The thing to know about quicksand is that it doesn’t swallow you immediately.

The thing to know about quicksand is that it doesn’t swallow you immediately. You sink slowly at first, so if you know what you’re doing, you can actually move across it safely. The trick is to distribute your weight and stay in motion, never standing still long enough to let it pull you under. If you thrash around in a panic you’ll accelerate your own descent. Freeze up and you’ll sink just as surely, only slower.

That metaphor represents what’s happening in the web industry right now. The ground that held firm for the past twenty years has gone soft and some people are at risk of sinking. I’ve seen colleagues thrashing against AI tools, insisting the work generated by AI will never be as good, accelerating their own descent. I’ve seen others frozen in denial, using the same workflows they've always used, hoping that if they just keep their heads down and do good work, they’ll be fine. But I've also seen a third group who’ve rewired how they work, using AI as a collaborator and force multiplier to achieve things that weren’t possible before, producing work at a level they wouldn’t have reached on their own.

The current reality for designers and developers is their profession is changing rapidly, following an extended period of nearly 20 years of following the same steps and applying the same processes over and over again.

Up until recently, whether designing for a website or an app, the designer’s role would start with some kind of initial research phase, then go through a wireframing phase, and end with a visual design phase that culminated in mockups and either a style guide or component library that would get handed off to a dev team to implement. If they were lucky they’d get asked to “do design QA” a week or two before launch, but otherwise they were not expected to go anywhere near the development process or god forbid contribute any code. Now, I understand why developers have resisted having designers be involved in the build phase. I have colleagues who have mild PTSD from having to fix designers’ hard-coded hacks that were used to achieve “pixel-perfect” results. But they’re going to have to get over that, fast.

We are now in living in a new world where generative AI has changed the game, like it or not, for everyone in the production chain. Large language models are now able to do a lot of the heavy lifting, do a lot of the synthesis, do a lot of the problem-solving, do a lot of the ideating, do a lot of the back-and-forth critiquing, and objectively analyzing patterns to produce higher fidelity, higher quality deliverables and artifacts in a fraction of the time with a fraction of the resources.

AI is able to look at the existing brand guidelines, digest the voice and tone documentation, and produce everything that normally requires a team of people to do. It all needs to be orchestrated of course but that requires just one or two really smart savvy people with the vision and an overall end-to-end understanding of how everything needs to fit together. AI is also able to write code really well now. And it’s able to pull together the components needed to build new pages directly from Figma and assemble them in a CMS.

At this point you don't need a team of developers anymore, though it’s probably a wise to have at least one good one to review the code the AI agents produce. You certainly don't need a team of writers and designers anymore. You just need one good editor or content person and one good designer, because ultimately taste matters and these things come down to subjective style choices and conscious decisions about what is “good.”

Two things have made this new paradigm possible.

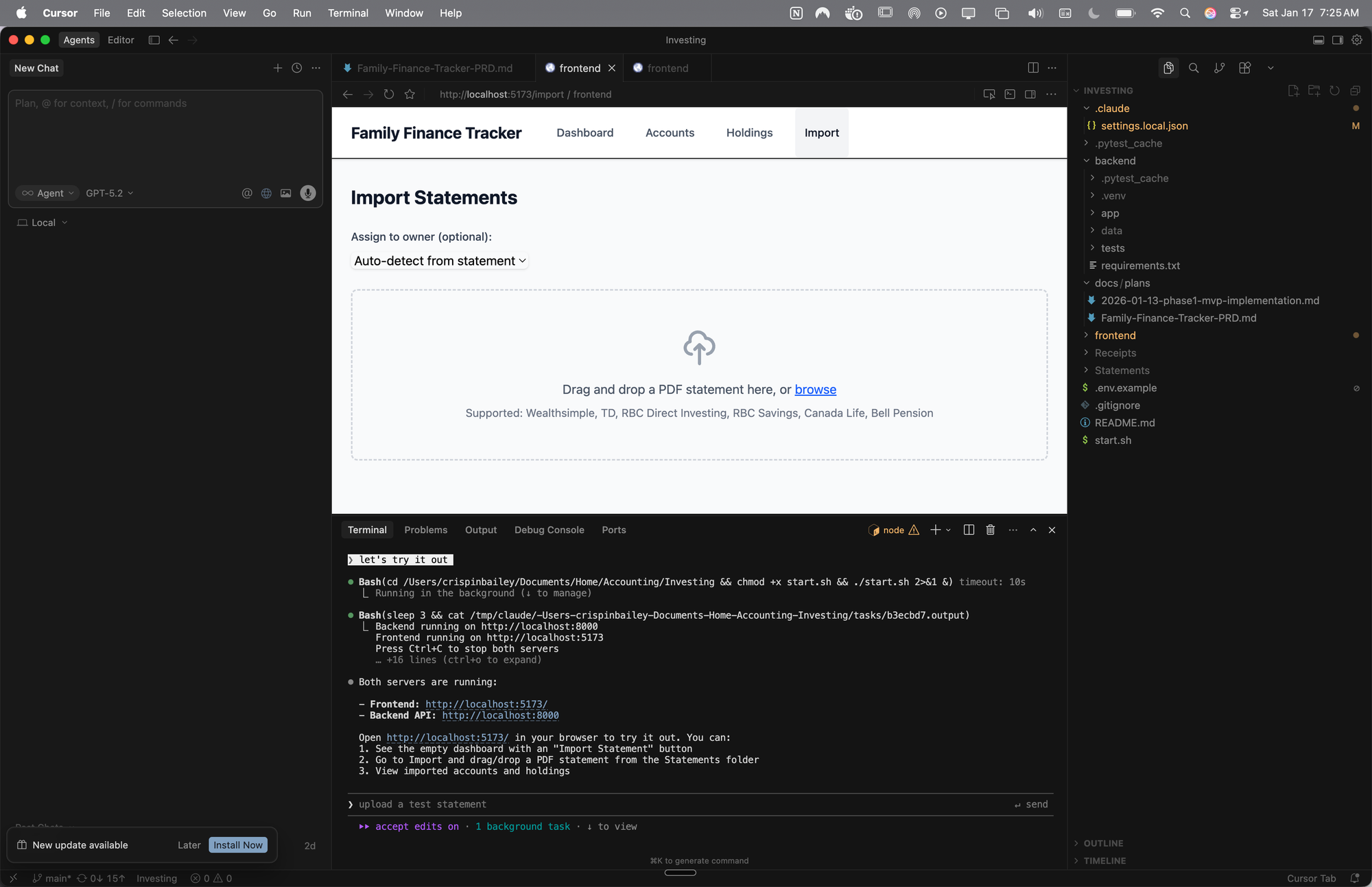

The first is Cursor. I know, I know. Cursor is a developer's tool. It's an IDE. It's what coders use to write software and work on code. But hear me out. Over the last six months, it has gotten way better and way easier to use as a designer who knows a little bit about code.

First, their agent mode is actually great now, with different modes (Ask, Plan, Debug, and Agent) to tap into, depending on your needs. Second, they added a visual design editor that lets designers click on a browser preview and make changes that the agent then converts into code changes. Third, is worktree support, which basically lets you have multiple LLMs running the same prompt in parallel so you can compare outputs. And you can use it with all the best models, including Cursor’s own Composer model.

And most significantly, all of this works with virtually any type of file on your computer that an LLM can read, not just code, which means you can use it to draft blog posts, create documentation, scan PDFs, analyze and update spreadsheets, generate charts, review screenshots, give feedback, etc. In other words the same software that developers have been using to write code has evolved to become a powerful tool for anyone to create, modify, organize, and publish all kinds of work with.

The other game changer is Claude Code. Over the past month or so my social feed and inbox have seen a steady increase in volume of people who have become obsessed with Claude Code's ability to do things that were previously either impossible or unlikely to turn out as hoped. This was in large part due to the release of the Opus 4.5 model, Anthropic's biggest and smartest yet, but even without it Claude Code represented a fundamentally different way of working with AI.

To understand why, you need to grasp the difference between chat-based AI and agentic AI. When you use the regular Claude interface, you're having a conversation. You describe a problem, Claude suggests a solution, you copy that solution somewhere and try it out, discover it doesn't quite work, go back to Claude, paste in the error message, get a revised suggestion, and repeat. It's helpful, but you're still the one doing all the actual work. You're the hands; Claude is the advisor looking over your shoulder.

Claude Code flips this relationship. It operates in what developers call an "agentic loop," meaning it doesn't just suggest code, it actually runs it. When something breaks, it sees the error, analyzes what went wrong, fixes the problem, and tries again. This cycle continues until the thing actually works. You're no longer copying and pasting between windows. You're describing what you want and watching it get built.

This works because Claude Code has genuine access to your system. It can navigate your entire file structure, read and modify files directly, run terminal commands, execute tests, manage git operations, and install dependencies. It operates like a developer with full access to your machine, not a consultant giving advice from a distance.

Even before Opus 4.5 arrived, Claude Code could do something that still feels a bit like magic: spawn multiple sub-agents to work on different parts of a problem in parallel. One agent might research an API while another refactors existing code while a third writes tests. They work simultaneously and then synthesize their results. For complex projects that would normally require coordinating across multiple people or context-switching constantly, this changes the equation entirely.

One of the persistent problems with AI coding assistants has been context degradation. You start a session, build up momentum and shared understanding, and then somewhere around the two-hour mark things start to get weird. The AI forgets decisions you made earlier. It contradicts itself. It starts suggesting things you already tried and rejected. This happens because of how context windows work: there's only so much conversation history the model can hold in memory at once, and when you hit that limit, things fall apart.

Claude Code addresses this through something called context compaction. When your conversation approaches the context limit, instead of hitting a wall or silently degrading, Claude Code intelligently summarizes the earlier parts of your session while preserving the important stuff: key decisions, file states, the current task and its requirements. You can trigger this manually with the /compact command or let it happen automatically. As of recent updates, compaction happens instantly rather than requiring a minute or two of waiting. The practical effect is that you can run genuinely long sessions without the drift and confusion that plagued earlier tools.

For context that needs to persist across sessions entirely, there's CLAUDE.md. This is a file that lives in your project directory containing the core information Claude should always know: your tech stack, architectural decisions, coding conventions, testing requirements, whatever context you'd otherwise have to re-explain every time you start a new conversation. It's essentially a persistent briefing document that doesn't consume your active conversation space.

Related but distinct are Skills, which Anthropic introduced in October 2025 and which Simon Willison has argued might be a bigger deal than MCP. Skills are folders containing instructions, scripts, and resources that define how Claude should handle specific types of tasks. The clever part is how they manage token efficiency: at the start of a session, Claude scans available skills and loads only a brief description of each one, consuming just a few dozen tokens. The full implementation, which might run to a thousand lines or more, only gets loaded when you actually request a task that skill can help with.

This on-demand loading pattern turns out to be transformative. You can have dozens of specialized skills available without burdening your startup context. A skill for creating LinkedIn-optimized PNGs. A skill for processing census data. A skill for following your organization's brand guidelines when generating documents. Each one encapsulates expert knowledge about how to approach a particular kind of work, and Claude automatically invokes the relevant skill based on what you're trying to accomplish. No manual selection required.

The practical effect is that you can package expertise into reusable modules. If your team has figured out the best way to handle database migrations, or write API documentation, or process a particular data format, that knowledge can live in a skill that any team member can access. Anthropic has published Agent Skills as an open standard, meaning they're designed to work across platforms, not just within Claude's ecosystem. For organizations trying to scale AI-assisted workflows while maintaining consistency, this is a significant development.

Then there's MCP, the Model Context Protocol, which Anthropic released as an open standard and which Microsoft has since described as "the USB-C for AI applications." MCP allows Claude Code to connect directly to external services through a standardized interface: GitHub, Slack, Notion, Figma, Sentry, databases, CI/CD pipelines, and hundreds of other tools. Instead of copying information between applications or manually orchestrating workflows, Claude Code can operate natively within your existing tool ecosystem. It can open pull requests, post Slack messages, review Figma files, query databases, and check error logs all without you ever leaving the terminal.

All of this existed before Opus 4.5. What the new model did was make everything work dramatically better. Opus 4.5 arrived with extended thinking enabled by default, which means it reasons through complex problems more thoroughly before acting. It follows instructions more precisely and uses significantly fewer tokens to accomplish the same tasks (Anthropic claims up to 65% fewer in some cases). The model that was already good at using sophisticated tools became exceptional at it.

This is why people have become obsessed with Claude Code. Not because any single feature is revolutionary, but because the combination of agentic execution, persistent context, parallel processing, intelligent memory management, and ecosystem integration has crossed the threshold to where the tool genuinely augments what any single person could accomplish. You describe what you want built. It gets built. You refine and direct. The gap between intention and implementation has narrowed to something that would have seemed implausible even a year ago.

The real unlock for me has been running both Cursor and Claude Code together. I have Claude Code running in Cursor's integrated terminal, handling the big agentic tasks that require multiple steps and file modifications. I have Cursor's own agents running alongside it, helping me plan approaches and answer questions about the codebase. The visual editor is there for me when I want to click on an element and adjust spacing or typography directly. And when I need to, I can still open up the code editor and make manual edits the old-fashioned way. All in one window. I get all the benefits of AI, with none of the loss of control that comes with most other vibe coding tools.

I honestly didn’t expect this to be so much fun. I used to code websites and iPhone apps, but it was always a slog. I hadn’t opened a code editor in over a decade. When AI coding tools started gaining traction, my first instinct was resistance. I had no intention of going back to staring at syntax errors and chasing down missing semicolons. But somewhere along the way, the dread turned into curiosity, and recent advances have made the daunting doable. And there’s a real thrill to working at the edge of what’s possible, to having built something you couldn’t have imagined building alone.

And the quicksand that’s swallowing others? Once you learn how to move across it, it starts to feel less like a trap and more like a trampoline. So if you’ve been holding back, now’s the time to make the leap. And if you’re not sure where to begin, the resources below are a good place to start. Good luck, and have fun!

Resources

- Free Claude code course

- Every’s guide to building agentic apps

- Cursor’s official learning resources and free workshops

- Claude Code official documentation

- Peter Yang explains Claude Skills in 15 minutes

- Jesse Vincent’s Superpowers Skills package for test-driven Claude Code development

Editing assistance provided by Claude. Cover image created with Midjourney.